Conversations

Learning to Live Together

Learning to Live Together

Learning to Live Together

Learning to Live Together

Learning to Live Together

(Or how to see the Big Picture)

(Or how to see the Big Picture)

(Or how to see the Big Picture)

(Or how to see the Big Picture)

(Or how to see the Big Picture)

"It was six men of Indostan

To learning much inclined,

Who went to see the Elephant

(Though all of them were blind),

That each by observation

Might satisfy his mind."

These are the opening lines of the poem The Blind Men and the Elephant by 19th century American poet John Godfrey Saxe. This poem brought to Western attention an ancient fable from the Buddist, Hindu and Jain traditions about the multifaceted nature of truth.

The story goes that six blind men who have never before encountered an elephant set out to describe this new phenomenon. When they finished their investigations they were each asked to describe the elephant.

The first man, who had examined a leg of the elephant pronounced with great conviction that he now could say with certainty that an elephant is just like a pillar. This pronouncement was met with loud disagreement from his fellow scholars. The man who had investigated the elephant's tail stepped forward declaring that it was clear that an elephant is like a rope. The man who had felt the ear dismissed these notions and said the elephant was clearly like a giant fan. These descriptions were in turn dismissed by the man who had felt the trunk as he was convinced that the elephant was very similar to the branch of a tree. The man who had investigated the elephant's belly listened to these descriptions and found them preposterous! It was so obvious to him that an elephant was like a solid wall he couldn't understand how his companions could say anything else. And finally, the man who had examined the elephant's tusk announced that they were all mistaken as there was no doubt that an elephant resembled nothing more closely than a solid pipe. The arguing began in earnest then, as John Godfrey Saxe put it in his poem -

"And so these men of Indostan

Disputed loud and long,

Each in his own opinion

Exceeding stiff and strong,

Though each was partly in the right,

And all were in the wrong!"

"It was six men of Indostan

To learning much inclined,

Who went to see the Elephant

(Though all of them were blind),

That each by observation

Might satisfy his mind."

These are the opening lines of the poem The Blind Men and the Elephant by 19th century American poet John Godfrey Saxe. This poem brought to Western attention an ancient fable from the Buddist, Hindu and Jain traditions about the multifaceted nature of truth.

The story goes that six blind men who have never before encountered an elephant set out to describe this new phenomenon. When they finished their investigations they were each asked to describe the elephant.

The first man, who had examined a leg of the elephant pronounced with great conviction that he now could say with certainty that an elephant is just like a pillar. This pronouncement was met with loud disagreement from his fellow scholars. The man who had investigated the elephant's tail stepped forward declaring that it was clear that an elephant is like a rope. The man who had felt the ear dismissed these notions and said the elephant was clearly like a giant fan. These descriptions were in turn dismissed by the man who had felt the trunk as he was convinced that the elephant was very similar to the branch of a tree. The man who had investigated the elephant's belly listened to these descriptions and found them preposterous! It was so obvious to him that an elephant was like a solid wall he couldn't understand how his companions could say anything else. And finally, the man who had examined the elephant's tusk announced that they were all mistaken as there was no doubt that an elephant resembled nothing more closely than a solid pipe. The arguing began in earnest then, as John Godfrey Saxe put it in his poem -

"And so these men of Indostan

Disputed loud and long,

Each in his own opinion

Exceeding stiff and strong,

Though each was partly in the right,

And all were in the wrong!"

"It was six men of Indostan

To learning much inclined,

Who went to see the Elephant

(Though all of them were blind),

That each by observation

Might satisfy his mind."

These are the opening lines of the poem The Blind Men and the Elephant by 19th century American poet John Godfrey Saxe. This poem brought to Western attention an ancient fable from the Buddist, Hindu and Jain traditions about the multifaceted nature of truth.

The story goes that six blind men who have never before encountered an elephant set out to describe this new phenomenon. When they finished their investigations they were each asked to describe the elephant.

The first man, who had examined a leg of the elephant pronounced with great conviction that he now could say with certainty that an elephant is just like a pillar. This pronouncement was met with loud disagreement from his fellow scholars. The man who had investigated the elephant's tail stepped forward declaring that it was clear that an elephant is like a rope. The man who had felt the ear dismissed these notions and said the elephant was clearly like a giant fan. These descriptions were in turn dismissed by the man who had felt the trunk as he was convinced that the elephant was very similar to the branch of a tree. The man who had investigated the elephant's belly listened to these descriptions and found them preposterous! It was so obvious to him that an elephant was like a solid wall he couldn't understand how his companions could say anything else. And finally, the man who had examined the elephant's tusk announced that they were all mistaken as there was no doubt that an elephant resembled nothing more closely than a solid pipe. The arguing began in earnest then, as John Godfrey Saxe put it in his poem -

"And so these men of Indostan

Disputed loud and long,

Each in his own opinion

Exceeding stiff and strong,

Though each was partly in the right,

And all were in the wrong!"

"It was six men of Indostan

To learning much inclined,

Who went to see the Elephant

(Though all of them were blind),

That each by observation

Might satisfy his mind."

These are the opening lines of the poem The Blind Men and the Elephant by 19th century American poet John Godfrey Saxe. This poem brought to Western attention an ancient fable from the Buddist, Hindu and Jain traditions about the multifaceted nature of truth.

The story goes that six blind men who have never before encountered an elephant set out to describe this new phenomenon. When they finished their investigations they were each asked to describe the elephant.

The first man, who had examined a leg of the elephant pronounced with great conviction that he now could say with certainty that an elephant is just like a pillar.

This pronouncement was met with loud disagreement from his fellow scholars.

The man who had investigated the elephant's tail stepped forward declaring that it was clear that an elephant is like a rope.

The man who had felt the ear dismissed these notions and said the elephant was clearly like a giant fan.

These descriptions were in turn dismissed by the man who had felt the trunk as he was convinced that the elephant was very similar to the branch of a tree.

The man who had investigated the elephant's belly listened to these descriptions and found them preposterous! It was so obvious to him that an elephant was like a solid wall he couldn't understand how his companions could say anything else.

And finally, the man who had examined the elephant's tusk announced that they were all mistaken as there was no doubt that an elephant resembled nothing more closely than a solid pipe.

The arguing began in earnest then, as John Godfrey Saxe put it in his poem -

"And so these men of Indostan

Disputed loud and long,

Each in his own opinion

Exceeding stiff and strong,

Though each was partly in the right,

And all were in the wrong!"

As individuals we each see the world through our own unique lens

As individuals we each see the world through our own unique lens

As individuals we each see the world through our own unique lens

As individuals we each see the world through our own unique lens

As individuals we each see the world through our own unique lens

Our nature, our nurture, our culture, our personalities, our education and attitudes all influence how we see things. Even things we’ve never seen before are coloured by our unique persepective and experience. So, while it may well be the case that truth is one and indivisible, that doesn’t mean that any of us ever perceives the truth in its entirety. None of us actually have the Big Picture. At best, if we're lucky, we'll glimpse part of the truth.

But what about things that are simply not true? Well, there is no doubt that not everything is true and that in searching for the truth we have to find ways to distinguish between truth and untruth. However, even when we are satisfied that we really have a view of the truth it is still just that, 'a view', and doesn't represent the whole truth. If we look at how perception operates, it becomes clear how many views, even of the same thing or the same situation, can all contain truth without negating or cancelling any other view.

Our nature, our nurture, our culture, our personalities, our education and attitudes all influence how we see things. Even things we’ve never seen before are coloured by our unique persepective and experience. So, while it may well be the case that truth is one and indivisible, that doesn’t mean that any of us ever perceives the truth in its entirety. None of us actually have the Big Picture. At best, if we're lucky, we'll glimpse part of the truth.

But what about things that are simply not true? Well, there is no doubt that not everything is true and that in searching for the truth we have to find ways to distinguish between truth and untruth. However, even when we are satisfied that we really have a view of the truth it is still just that, 'a view', and doesn't represent the whole truth. If we look at how perception operates, it becomes clear how many views, even of the same thing or the same situation, can all contain truth without negating or cancelling any other view.

Our nature, our nurture, our culture, our personalities, our education and attitudes all influence how we see things. Even things we’ve never seen before are coloured by our unique persepective and experience. So, while it may well be the case that truth is one and indivisible, that doesn’t mean that any of us ever perceives the truth in its entirety. None of us actually have the Big Picture. At best, if we're lucky, we'll glimpse part of the truth.

But what about things that are simply not true? Well, there is no doubt that not everything is true and that in searching for the truth we have to find ways to distinguish between truth and untruth. However, even when we are satisfied that we really have a view of the truth it is still just that, 'a view', and doesn't represent the whole truth. If we look at how perception operates, it becomes clear how many views, even of the same thing or the same situation, can all contain truth without negating or cancelling any other view.

Our nature, our nurture, our culture, our personalities, our education and attitudes all influence how we see things. Even things we’ve never seen before are coloured by our unique persepective and experience. So, while it may well be the case that truth is one and indivisible, that doesn’t mean that any of us ever perceives the truth in its entirety. None of us actually have the Big Picture. At best, if we're lucky, we'll glimpse part of the truth.

But what about things that are simply not true? Well, there is no doubt that not everything is true and that in searching for the truth we have to find ways to distinguish between truth and untruth. However, even when we are satisfied that we really have a view of the truth it is still just that, 'a view', and doesn't represent the whole truth. If we look at how perception operates, it becomes clear how many views, even of the same thing or the same situation, can all contain truth without negating or cancelling any other view.

Our nature, our nurture, our culture, our personalities, our education and attitudes all influence how we see things. Even things we’ve never seen before are coloured by our unique persepective and experience.

So, while it may well be the case that truth is one and indivisible, that doesn’t mean that any of us ever perceives the truth in its entirety. None of us actually have the Big Picture. At best, if we're lucky, we'll glimpse part of the truth.

But what about things that are simply not true? Well, there is no doubt that not everything is true and that in searching for the truth we have to find ways to distinguish between truth and untruth. However, even when we are satisfied that we really have a view of the truth it is still just that, 'a view', and doesn't represent the whole truth.

If we look at how perception operates, it becomes clear how many views, even of the same thing or the same situation, can all contain truth without negating or cancelling any other view.

In an interview he gave in the 1960s, physicist David Bohm explained how he understood perception to work -

“The point about perception is that it is a dynamic process…the more views we get that we can integrate and make coherent the deeper our understanding of the reality... Every view is limited, it’s like a mirror looking this way, each one gives a limited view…We must distinguish between correct appearances and incorrect appearances…if an appearance is correct it is in some way related to the reality but it is evidently not the reality…" (1)

In other words, while our view may be related to the reality of a thing or situation, it isn't a definitive description of reality. To get as close as possible to the reality or truth we need to incorporate as many different views as possible. If it’s really truth that we’re after our limited grasp won’t bother us and we’ll be happy to consult with others to deepen our understanding of reality.

In an interview he gave in the 1960s, physicist David Bohm explained how he understood perception to work -

“The point about perception is that it is a dynamic process…the more views we get that we can integrate and make coherent the deeper our understanding of the reality... Every view is limited, it’s like a mirror looking this way, each one gives a limited view…We must distinguish between correct appearances and incorrect appearances…if an appearance is correct it is in some way related to the reality but it is evidently not the reality…" (1)

In other words, while our view may be related to the reality of a thing or situation, it isn't a definitive description of reality. To get as close as possible to the reality or truth we need to incorporate as many different views as possible. If it’s really truth that we’re after our limited grasp won’t bother us and we’ll be happy to consult with others to deepen our understanding of reality.

In an interview he gave in the 1960s, physicist David Bohm explained how he understood perception to work -

“The point about perception is that it is a dynamic process…the more views we get that we can integrate and make coherent the deeper our understanding of the reality... Every view is limited, it’s like a mirror looking this way, each one gives a limited view…We must distinguish between correct appearances and incorrect appearances…if an appearance is correct it is in some way related to the reality but it is evidently not the reality…" (1)

In other words, while our view may be related to the reality of a thing or situation, it isn't a definitive description of reality. To get as close as possible to the reality or truth we need to incorporate as many different views as possible. If it’s really truth that we’re after our limited grasp won’t bother us and we’ll be happy to consult with others to deepen our understanding of reality.

In an interview he gave in the 1960s, physicist David Bohm explained how he understood perception to work -

“The point about perception is that it is a dynamic process…the more views we get that we can integrate and make coherent the deeper our understanding of the reality... Every view is limited, it’s like a mirror looking this way, each one gives a limited view…We must distinguish between correct appearances and incorrect appearances…if an appearance is correct it is in some way related to the reality but it is evidently not the reality…" (1)

In other words, while our view may be related to the reality of a thing or situation, it isn't a definitive description of reality. To get as close as possible to the reality or truth we need to incorporate as many different views as possible. If it’s really truth that we’re after our limited grasp won’t bother us and we’ll be happy to consult with others to deepen our understanding of reality.

In an interview he gave in the 1960s, physicist David Bohm explained how he understood perception to work -

“The point about perception is that it is a dynamic process…the more views we get that we can integrate and make coherent the deeper our understanding of the reality... Every view is limited, it’s like a mirror looking this way, each one gives a limited view…We must distinguish between correct appearances and incorrect appearances…if an appearance is correct it is in some way related to the reality but it is evidently not the reality…" (1)

In other words, while our view may be related to the reality of a thing or situation, it isn't a definitive description of reality.

To get as close as possible to the reality or truth we need to incorporate as many different views as possible.

If it’s really truth that we’re after our limited grasp won’t bother us and we’ll be happy to consult with others to deepen our understanding of reality.

When we insist that the fragments of truth to which we have access represent the totality of the Big Picture there are always problems. The most obvious difficulty with this approach is that it is an obstacle to finding the whole truth about anything. But possibly even more serious than that is the fact that it causes a polarisation of views that can create divisions between people.

This type of polarisation is having disastrous consequences in our societies as radicalisation (whether political or religious) grows and erupts into violence and social unrest. There are also less obvious but quite serious consequences when we insist on any exclusive orthodoxy (no matter what that is) and ignore or dismiss voices that don't support our status quo.

When we insist that the fragments of truth to which we have access represent the totality of the Big Picture there are always problems. The most obvious difficulty with this approach is that it is an obstacle to finding the whole truth about anything. But possibly even more serious than that is the fact that it causes a polarisation of views that can create divisions between people.

This type of polarisation is having disastrous consequences in our societies as radicalisation (whether political or religious) grows and erupts into violence and social unrest. There are also less obvious but quite serious consequences when we insist on any exclusive orthodoxy (no matter what that is) and ignore or dismiss voices that don't support our status quo.

When we insist that the fragments of truth to which we have access represent the totality of the Big Picture there are always problems. The most obvious difficulty with this approach is that it is an obstacle to finding the whole truth about anything. But possibly even more serious than that is the fact that it causes a polarisation of views that can create divisions between people.

This type of polarisation is having disastrous consequences in our societies as radicalisation (whether political or religious) grows and erupts into violence and social unrest. There are also less obvious but quite serious consequences when we insist on any exclusive orthodoxy (no matter what that is) and ignore or dismiss voices that don't support our status quo.

When we insist that the fragments of truth to which we have access represent the totality of the Big Picture there are always problems. The most obvious difficulty with this approach is that it is an obstacle to finding the whole truth about anything. But possibly even more serious than that is the fact that it causes a polarisation of views that can create divisions between people.

This type of polarisation is having disastrous consequences in our societies as radicalisation (whether political or religious) grows and erupts into violence and social unrest. There are also less obvious but quite serious consequences when we insist on any exclusive orthodoxy (no matter what that is) and ignore or dismiss voices that don't support our status quo.

When we insist that the fragments of truth to which we have access represent the totality of the Big Picture there are always problems.

The most obvious difficulty with this approach is that it is an obstacle to finding the whole truth about anything. But possibly even more serious than that is the fact that it causes a polarisation of views that can create divisions between people.

This type of polarisation is having disastrous consequences in our societies as radicalisation (whether political or religious) grows and erupts into violence and social unrest.

There are also less obvious but quite serious consequences when we insist on any exclusive orthodoxy (no matter what that is) and ignore or dismiss voices that don't support our status quo.

How many of us are inclined to think that those who don't agree with us are either stupid or bad?

How many of us are inclined to think that those who don't agree with us are either stupid or bad?

How many of us are inclined to think that those who don't agree with us are either stupid or bad?

How many of us are inclined to think that those who don't agree with us are either stupid or bad?

How many of us are inclined to think that those who don't agree with us are either stupid or bad?

Many so called debates nowadays are simply each side hanging on to their views and engaging in slagging matches where they attack and undermine each other. Everyone digs in and tries to defend their position with no real interest in finding the truth or solutions to problems. The debated issues become polarised and all of the nuances of real life and real human situations are missing.

Belief (and this includes all sorts of belief, including having no fixed beliefs) is such an intrinsic part of identity that challenges to our beliefs often feel like attacks on us ourselves. This can cause us to feel we have to defend our beliefs as though we are being personally attacked and not just defending an idea. In the most serious cases it can cause us to defend our beliefs with violence. At the very least it lends itself to fear, entrenchment and othering.

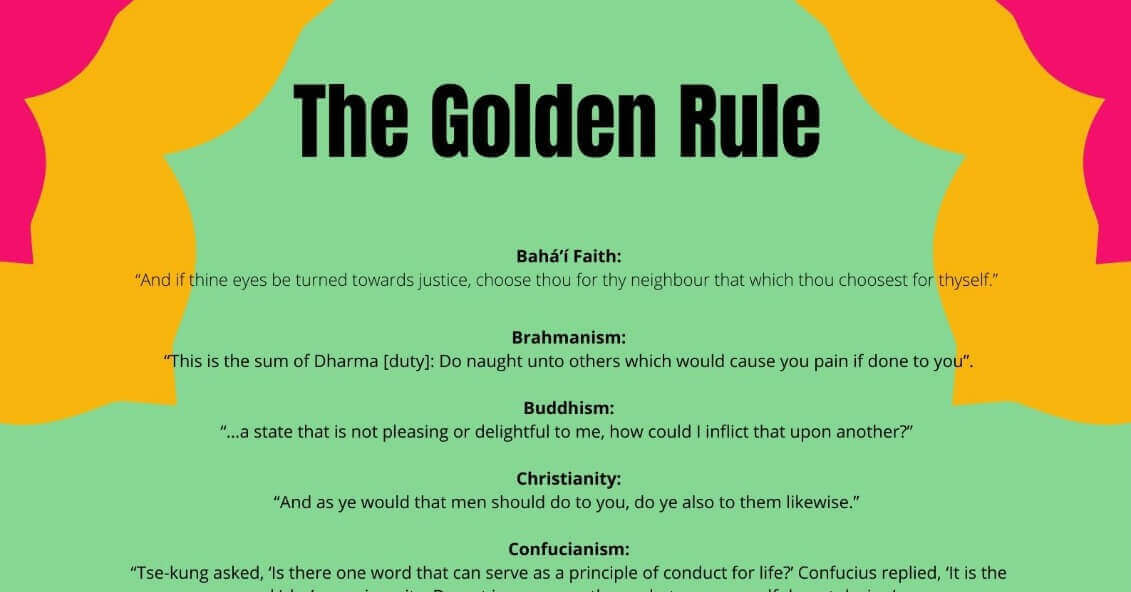

Insisting that any one belief system - religious or otherwise - is the only one acceptable in a society can bring many problems. As well as hanging on to a fragment of truth and renaming it the Big Picture, it also necessarily cuts itself off from the many benefits available from diversity. Just as biodiversity is a characteristic of the health of our natural environment, ethnic, religious, cultural and viewpoint diversity contribute to the health of our societies.

Many so called debates nowadays are simply each side hanging on to their views and engaging in slagging matches where they attack and undermine each other. Everyone digs in and tries to defend their position with no real interest in finding the truth or solutions to problems. The debated issues become polarised and all of the nuances of real life and real human situations are missing.

Belief (and this includes all sorts of belief, including having no fixed beliefs) is such an intrinsic part of identity that challenges to our beliefs often feel like attacks on us ourselves. This can cause us to feel we have to defend our beliefs as though we are being personally attacked and not just defending an idea. In the most serious cases it can cause us to defend our beliefs with violence. At the very least it lends itself to fear, entrenchment and othering.

Insisting that any one belief system - religious or otherwise - is the only one acceptable in a society can bring many problems. As well as hanging on to a fragment of truth and renaming it the Big Picture, it also necessarily cuts itself off from the many benefits available from diversity. Just as biodiversity is a characteristic of the health of our natural environment, ethnic, religious, cultural and viewpoint diversity contribute to the health of our societies.

Many so called debates nowadays are simply each side hanging on to their views and engaging in slagging matches where they attack and undermine each other. Everyone digs in and tries to defend their position with no real interest in finding the truth or solutions to problems. The debated issues become polarised and all of the nuances of real life and real human situations are missing.

Belief (and this includes all sorts of belief, including having no fixed beliefs) is such an intrinsic part of identity that challenges to our beliefs often feel like attacks on us ourselves. This can cause us to feel we have to defend our beliefs as though we are being personally attacked and not just defending an idea. In the most serious cases it can cause us to defend our beliefs with violence. At the very least it lends itself to fear, entrenchment and othering.

Insisting that any one belief system - religious or otherwise - is the only one acceptable in a society can bring many problems. As well as hanging on to a fragment of truth and renaming it the Big Picture, it also necessarily cuts itself off from the many benefits available from diversity. Just as biodiversity is a characteristic of the health of our natural environment, ethnic, religious, cultural and viewpoint diversity contribute to the health of our societies.

Many so called debates nowadays are simply each side hanging on to their views and engaging in slagging matches where they attack and undermine each other. Everyone digs in and tries to defend their position with no real interest in finding the truth or solutions to problems. The debated issues become polarised and all of the nuances of real life and real human situations are missing.

Belief (and this includes all sorts of belief, including having no fixed beliefs) is such an intrinsic part of identity that challenges to our beliefs often feel like attacks on us ourselves. This can cause us to feel we have to defend our beliefs as though we are being personally attacked and not just defending an idea. In the most serious cases it can cause us to defend our beliefs with violence. At the very least it lends itself to fear, entrenchment and othering.

Insisting that any one belief system - religious or otherwise - is the only one acceptable in a society can bring many problems. As well as hanging on to a fragment of truth and renaming it the Big Picture, it also necessarily cuts itself off from the many benefits available from diversity. Just as biodiversity is a characteristic of the health of our natural environment, ethnic, religious, cultural and viewpoint diversity contribute to the health of our societies.

Many so called debates nowadays are simply each side hanging on to their views and engaging in slagging matches where they attack and undermine each other. Everyone digs in and tries to defend their position with no real interest in finding the truth or solutions to problems. The debated issues become polarised and all of the nuances of real life and real human situations are missing.

Belief (and this includes all sorts of belief, including having no fixed beliefs) is such an intrinsic part of identity that challenges to our beliefs often feel like attacks on us ourselves.

This can cause us to feel we have to defend our beliefs as though we are being personally attacked and not just defending an idea. In the most serious cases it can cause us to defend our beliefs with violence. At the very least it lends itself to fear, entrenchment and othering.

Insisting that any one belief system - religious or otherwise - is the only one acceptable in a society can bring many problems. As well as hanging on to a fragment of truth and renaming it the Big Picture, it also necessarily cuts itself off from the many benefits available from diversity.

Just as biodiversity is a characteristic of the health of our natural environment, ethnic, religious, cultural and viewpoint diversity contribute to the health of our societies.

Finding ways to foster unity in diversity is a crucial key to the well-being of society.

Finding ways to foster unity in diversity is a crucial key to the well-being of society.

Finding ways to foster unity in diversity is a crucial key to the well-being of society.

Finding ways to foster unity in diversity is a crucial key to the well-being of society.

Finding ways to foster unity in diversity is a crucial key to the well-being of society.

The Bahá'í Writings compare humanity to a human body where each of the millions of cells work together and their diverse form and function is the secret to our health and wellbeing. This diversity is something not just to be tolerated but to be desired. If we look at the differences between us in new ways we might find, to our surpise, that these very differences contain the raw material we need to unify us. As Heiner Bielefeldt, Professor of Human Rights and Human Rights Policy at the University of Erlangen and former UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief, puts it,

"People can have most different views on the ultimate meaning of life, on the existence or non-existence of a divine being, on how to achieve happiness for themselves and for their fellow humans and on countless other questions—is not this very diversity in itself a manifestation of moral earnestness? Should we not respect such diversity also beyond the positions that we personally think to be true or at least reasonable? And cannot this respect become the common normative denominator on which to base a peaceful coexistence?" (2)

The Bahá'í Writings compare humanity to a human body where each of the millions of cells work together and their diverse form and function is the secret to our health and wellbeing. This diversity is something not just to be tolerated but to be desired. If we look at the differences between us in new ways we might find, to our surpise, that these very differences contain the raw material we need to unify us. As Heiner Bielefeldt, Professor of Human Rights and Human Rights Policy at the University of Erlangen and former UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief, puts it,

"People can have most different views on the ultimate meaning of life, on the existence or non-existence of a divine being, on how to achieve happiness for themselves and for their fellow humans and on countless other questions—is not this very diversity in itself a manifestation of moral earnestness? Should we not respect such diversity also beyond the positions that we personally think to be true or at least reasonable? And cannot this respect become the common normative denominator on which to base a peaceful coexistence?" (2)

The Bahá'í Writings compare humanity to a human body where each of the millions of cells work together and their diverse form and function is the secret to our health and wellbeing. This diversity is something not just to be tolerated but to be desired. If we look at the differences between us in new ways we might find, to our surpise, that these very differences contain the raw material we need to unify us. As Heiner Bielefeldt, Professor of Human Rights and Human Rights Policy at the University of Erlangen and former UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief, puts it,

"People can have most different views on the ultimate meaning of life, on the existence or non-existence of a divine being, on how to achieve happiness for themselves and for their fellow humans and on countless other questions—is not this very diversity in itself a manifestation of moral earnestness? Should we not respect such diversity also beyond the positions that we personally think to be true or at least reasonable? And cannot this respect become the common normative denominator on which to base a peaceful coexistence?" (2)

The Bahá'í Writings compare humanity to a human body where each of the millions of cells work together and their diverse form and function is the secret to our health and wellbeing. This diversity is something not just to be tolerated but to be desired. If we look at the differences between us in new ways we might find, to our surpise, that these very differences contain the raw material we need to unify us. As Heiner Bielefeldt, Professor of Human Rights and Human Rights Policy at the University of Erlangen and former UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief, puts it,

"People can have most different views on the ultimate meaning of life, on the existence or non-existence of a divine being, on how to achieve happiness for themselves and for their fellow humans and on countless other questions—is not this very diversity in itself a manifestation of moral earnestness? Should we not respect such diversity also beyond the positions that we personally think to be true or at least reasonable? And cannot this respect become the common normative denominator on which to base a peaceful coexistence?" (2)

The Bahá'í Writings compare humanity to a human body where each of the millions of cells work together and their diverse form and function is the secret to our health and wellbeing. This diversity is something not just to be tolerated but to be desired.

If we look at the differences between us in new ways we might find, to our surpise, that these very differences contain the raw material we need to unify us.

As Heiner Bielefeldt, Professor of Human Rights and Human Rights Policy at the University of Erlangen and former UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief, puts it,

"People can have most different views on the ultimate meaning of life, on the existence or non-existence of a divine being, on how to achieve happiness for themselves and for their fellow humans and on countless other questions—is not this very diversity in itself a manifestation of moral earnestness? Should we not respect such diversity also beyond the positions that we personally think to be true or at least reasonable? And cannot this respect become the common normative denominator on which to base a peaceful coexistence?" (2)

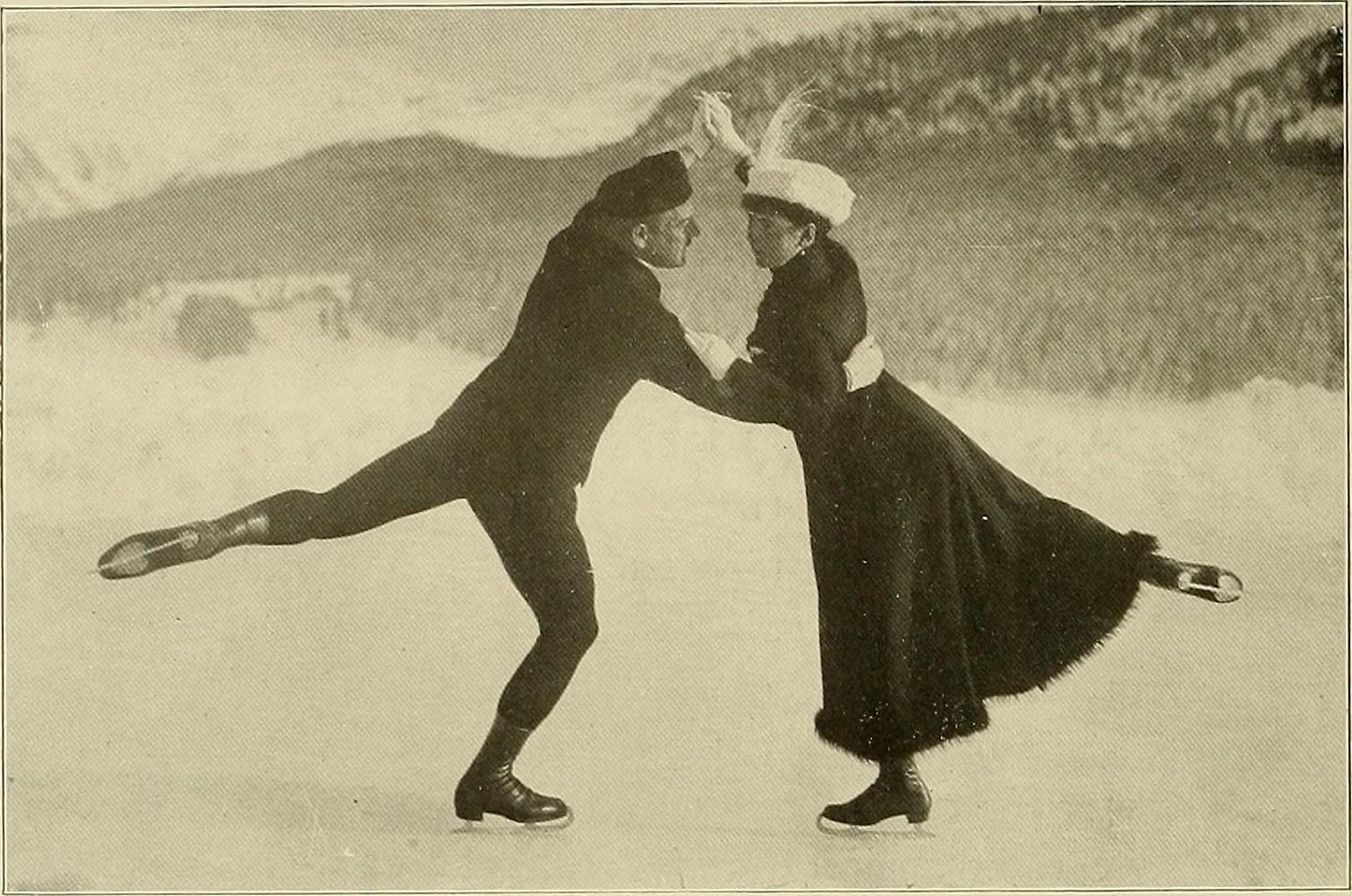

Let's Dance?

Let's Dance?

Let's Dance?

Let's Dance?

Let's Dance?

Learning how to work and associate, "...beyond the positions that we personally think to be true or reasonable," is a skill. Like many other skills such as dancing, reading or driving this skill needs to be structured and learned and acquired by practice.

Learning how to work and associate, "...beyond the positions that we personally think to be true or reasonable," is a skill. Like many other skills such as dancing, reading or driving this skill needs to be structured and learned and acquired by practice.

Learning how to work and associate, "...beyond the positions that we personally think to be true or reasonable," is a skill. Like many other skills such as dancing, reading or driving this skill needs to be structured and learned and acquired by practice.

Learning how to work and associate, "...beyond the positions that we personally think to be true or reasonable," is a skill. Like many other skills such as dancing, reading or driving this skill needs to be structured and learned and acquired by practice.

Learning how to work and associate, "...beyond the positions that we personally think to be true or reasonable," is a skill. Like many other skills such as dancing, reading or driving this skill needs to be structured and learned and acquired by practice.

Defining the structures in an endeavour like this is tricky and throws up many difficult questions - not least of which is the distinction between free speech versus hate speech. However, it's an endeavour worth undertaking if we are interested in finding a viable alternative to the polarisation of discourses, viewpoints and ideologies and the resulting alienation of sections of our societies.

If we learn to work together and each of us brings our fragments of truth to the table, perhaps we can develop a different type of status quo that sees every kind of diversity as an advantage to us as individuals and societies, notwithstanding the discomfort that may go with it. Given our limitations as human beings we're unlikely to ever complete the puzzle that is the Big Picture, but that won't matter. What will matter is that we will have developed respect for how others see the world and will be working together to find the truth.

"Sometimes the sun rises from the centre of the horizon, then in summer it rises farther north, in winter farther south—but it is always the self-same sun, however different are the points of its rising. In like manner truth is one, although its manifestations may be very different." (3)

Defining the structures in an endeavour like this is tricky and throws up many difficult questions - not least of which is the distinction between free speech versus hate speech. However, it's an endeavour worth undertaking if we are interested in finding a viable alternative to the polarisation of discourses, viewpoints and ideologies and the resulting alienation of sections of our societies.

If we learn to work together and each of us brings our fragments of truth to the table, perhaps we can develop a different type of status quo that sees every kind of diversity as an advantage to us as individuals and societies, notwithstanding the discomfort that may go with it. Given our limitations as human beings we're unlikely to ever complete the puzzle that is the Big Picture, but that won't matter. What will matter is that we will have developed respect for how others see the world and will be working together to find the truth.

"Sometimes the sun rises from the centre of the horizon, then in summer it rises farther north, in winter farther south—but it is always the self-same sun, however different are the points of its rising.In like manner truth is one, although its manifestations may be very different." (3)

Defining the structures in an endeavour like this is tricky and throws up many difficult questions - not least of which is the distinction between free speech versus hate speech. However, it's an endeavour worth undertaking if we are interested in finding a viable alternative to the polarisation of discourses, viewpoints and ideologies and the resulting alienation of sections of our societies.

If we learn to work together and each of us brings our fragments of truth to the table, perhaps we can develop a different type of status quo that sees every kind of diversity as an advantage to us as individuals and societies, notwithstanding the discomfort that may go with it. Given our limitations as human beings we're unlikely to ever complete the puzzle that is the Big Picture, but that won't matter. What will matter is that we will have developed respect for how others see the world and will be working together to find the truth.

"Sometimes the sun rises from the centre of the horizon, then in summer it rises farther north, in winter farther south—but it is always the self-same sun, however different are the points of its rising. In like manner truth is one, although its manifestations may be very different." (3)

Defining the structures in an endeavour like this is tricky and throws up many difficult questions - not least of which is the distinction between free speech versus hate speech. However, it's an endeavour worth undertaking if we are interested in finding a viable alternative to the polarisation of discourses, viewpoints and ideologies and the resulting alienation of sections of our societies.

If we learn to work together and each of us brings our fragments of truth to the table, perhaps we can develop a different type of status quo that sees every kind of diversity as an advantage to us as individuals and societies, notwithstanding the discomfort that may go with it. Given our limitations as human beings we're unlikely to ever complete the puzzle that is the Big Picture, but that won't matter. What will matter is that we will have developed respect for how others see the world and will be working together to find the truth.

"Sometimes the sun rises from the centre of the horizon, then in summer it rises farther north, in winter farther south—but it is always the self-same sun, however different are the points of its rising. In like manner truth is one, although its manifestations may be very different." (3)

Defining the structures in an endeavour like this is tricky and throws up many difficult questions - not least of which is the distinction between free speech versus hate speech. However, it's an endeavour worth undertaking if we are interested in finding a viable alternative to the polarisation of discourses, viewpoints and ideologies and the resulting alienation of sections of our societies.

If we learn to work together and each of us brings our fragments of truth to the table, perhaps we can develop a different type of status quo that sees every kind of diversity as an advantage to us as individuals and societies, notwithstanding the discomfort that may go with it.

Given our limitations as human beings we're unlikely to ever complete the puzzle that is the Big Picture, but that won't matter. What will matter is that we will have developed respect for how others see the world and will be working together to find the truth.

"Sometimes the sun rises from the centre of the horizon, then in summer it rises farther north, in winter farther south—but it is always the self-same sun, however different are the points of its rising. In like manner truth is one, although its manifestations may be very different." (3)

References

References

(1) David Bohm interview - Youtube

(2) Freedom of Religion or Belief—A Human Right under Pressure - Heiner Bielefeldt

Oxford Journal of Law and Religion, Volume 1, Issue 1, April 2012, Pages 15–35,

Published: 11 January 2012

(1) David Bohm interview - Youtube

(2) Freedom of Religion or Belief—A Human Right under Pressure - Heiner Bielefeldt

Oxford Journal of Law and Religion, Volume 1, Issue 1, April 2012, Pages 15–35,

Published: 11 January 2012

(3) Paris Talks, 'Abdu'l-Bahá p.128

(1) David Bohm interview - YouTube

(2) Freedom of Religion or Belief—A Human Right under Pressure - Heiner Bielefeldt

Oxford Journal of Law and Religion, Volume 1, Issue 1, April 2012, Pages 15–35,

Published: 11 January 2012

Some more Conversations

Some more Conversations

Some more Conversations

© 182 / 2026 | The National Spiritual Assembly of The Bahá'ís of Ireland | info@bahai.ie | (01) 6683 150 | CHY 05920 | RCN:20009724

© 182 / 2026 | The National Spiritual Assembly of The Bahá'ís of Ireland | info@bahai.ie | (01) 6683 150 | CHY 05920 | RCN:20009724

© 182 / 2026 | The National Spiritual Assembly of The Bahá'ís of Ireland | info@bahai.ie | (01) 6683 150 | CHY 05920 | RCN:20009724

© 182 / 2026 | The National Spiritual Assembly of The Bahá'ís of Ireland | info@bahai.ie | (01) 6683 150 | CHY 05920 | RCN:20009724